they’re stuck in my head. I can’t say them, regardless of how hard I try!

That was the first sign I had that something was going wrong — terribly wrong — with my mind and

body!

That was the first sign I had that something was going wrong — terribly wrong — with my mind and

body!

I had no warning whatsoever, not even the slightest suggestion. I couldn’t tell my wife — who, in my mind’s eye, was sitting next to me (she wasn’t) — what was going on. I was frozen; I couldn’t move a muscle — not my mouth — not my head — not my feet — nothing. I couldn’t even hold a pen to write my wife a note. I was trapped inside my mind.

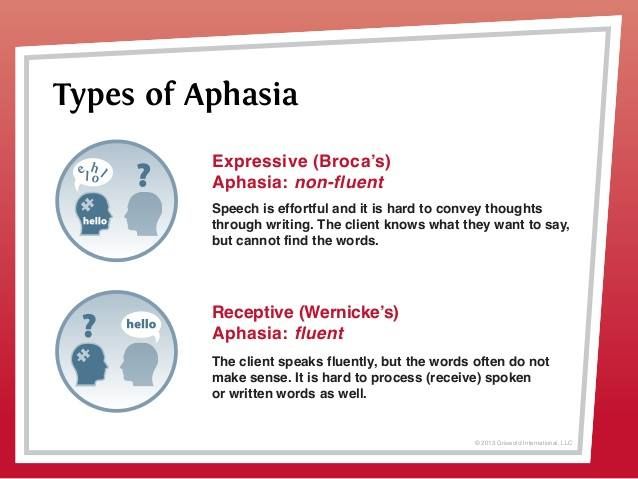

Aphasia is a communication disorder. It results from damage to the parts of the brain that process language (typically in the left half of the brain). Aphasia may cause difficulties in speaking, listening, reading, and writing, but does not affect intelligence. Aphasia can be permanent or only a temporary condition.

In 2001, Dad went to the hospital for brain surgery for normal pressure hydrocephalus, a correctable form of dementia.

The hospital called at midnight, waking me just 14 hours after his surgery. Dad’s nurses wanted to know if I had given him morphine. Still half asleep, I explained that wasn’t possible — I’m not a doctor. Mom isn’t either. Then they wanted to know if we’d asked anyone else to give it to him. Puzzled, I said, “No, of course not! Why are you asking this?” Their response: “Well someone did; he’s hallucinating. Whenever we go into his room, he gets extremely agitated and tries to grab things out of the air.”

Later, satisfied that I had nothing to do with the morphine, they told us it wasn’t necessary for Mom and I to come to the hospital in the middle of the night. They assured us they’d keep a close eye on him.

The next morning, Mom and I went directly to his room. He was still extremely agitated, motioning for something by moving his hand in the air. Then, he grew even more agitated, kicking off his sheet because both we and his nurses didn’t know how to respond.

I finally realized that he wanted me to come closer to him — close enough for him to whisper in my ear. But no sound came out. That made him even more frustrated, thrashing around in his bed. As earlier, his nurses had no clues as to what to do next.

Shortly after that, a tech took him to the radiology department for an x-ray of his back. However, because of his agitation, the technician asked me to hold him in place. They hoped that would help him be calmer when they took the x-ray. After putting on a lead apron for protection, they showed me how to hold Dad. I did, but he suddenly went limp as a rag while they took the x-ray. He never moved a muscle again on his own. In effect, he died in my arms that morning.

What went wrong? He had a massive, long-lasting stroke that wasn’t recognized until two days later. He knew something bad was happening and wanted only to get someone’s attention to fix the problem while they could. But, the hospital’s staff were not, in his mind, paying any attention to him at this critical time. And, he continually got more and more frustrated and agitated with them until his brain was filled with more blood than it could take, and then passed away. The cause? He had a hemorrhage that started at the spot where he had his brain surgery. His stroke had first attacked the area of his brain that gave him the ability to speak.

So … now, after being trapped inside my own head with no ability to communicate, I understood just how frustrating aphasia is. But, obviously, I was luckier. Shortly after my aphasia began, I passed out, was taken to neurological ICU and woke up two days later in neurological rehab. Best of all, I had no brain damage.

About 25% to 40% of stroke survivors have some form of aphasia. But, aphasia is not like Alzheimer’s disease. For people with aphasia it is the ability to access ideas and thoughts through language — not the ideas and thoughts themselves — that is disrupted. But because people with aphasia have difficulty communicating, others often mistakenly assume they are mentally ill or have mental retardation.

How to Communicate with Someone Who Has Aphasia

Outwardly, advanced Alzheimer’s and aphasia can present the same symptom: the inability to communicate. And, both can be handled in much the same way by caregivers. … Continue Reading →

Additional Resources:

- Aphasia Creates Language Barriers that Require Rehabilitation

- Aphasia FAQs, National Aphasia Association